Queer love at the end of the world: ‘The Last of Us’ just gave us the best episode of television in a long, long time

AwardsWatch TV Editor Tyler Doster talked to ‘The Last of Us’ director Peter Hoar and cinematographer Eben Bolter about episode three of the series and looks at telling queer stories of love

The pilot episode of The Last of Us is a brutal, true-to-the-source-material adaptation that blends the original video game’s depiction of dread and violence with the medium of film’s ability to frame scenes differently to give better exposition for the story. While the original game was lauded upon release due to its emotional storytelling and realistic world-building, the new HBO series is able to expand upon that story by providing audiences with more context and details into the characters that have already been created by Neil Druckmann. At the end of the premiere episode, while Joel and Tess begin their mission of delivering Ellie to other members of the Fireflies, the scenes shift back to Tess and Joel’s apartment. Joel’s radio turns on and the opening notes of Depeche Mode’s 1987 track, “Never Let Me Down Again,” begin, the scene asking a question of the audience: is something wrong?

It is revealed earlier in the first episode that Joel uses the radio as a form of communication with his smuggler friends, Bill and Frank. Not long after arriving at Joel’s apartment, Ellie finds a book that has a piece of paper containing radio codes on it, all relating to music: 60s music means “nothing in,” 70s music signals “new stock,” while 80s has a mysterious “X” next to it. The next time Joel takes a nap and awakens, Ellie mentions to him that “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” a song released in 1984, had been playing on the radio. Joel’s negative reaction to hearing this alerts Ellie that 80s music is a distress signal. At the end of the first episode, when Depeche Mode’s song begins, anyone who recognized the music probably realized immediately that something was wrong. As the credits begin rolling during the episode’s conclusion, the opening lyrics are sung over the names of crew members: “I’m taking a ride with my best friend / I hope he never lets me down again.” Not only is the song’s year significant to the story, but the lyrics can also be taken realistically when given the context of what has happened with Bill and Frank. Thus, the third episode (aptly titled “Long Long Time”), which premiered tonight on HBO, begins its 75-minute ode to queer love in a broken world.

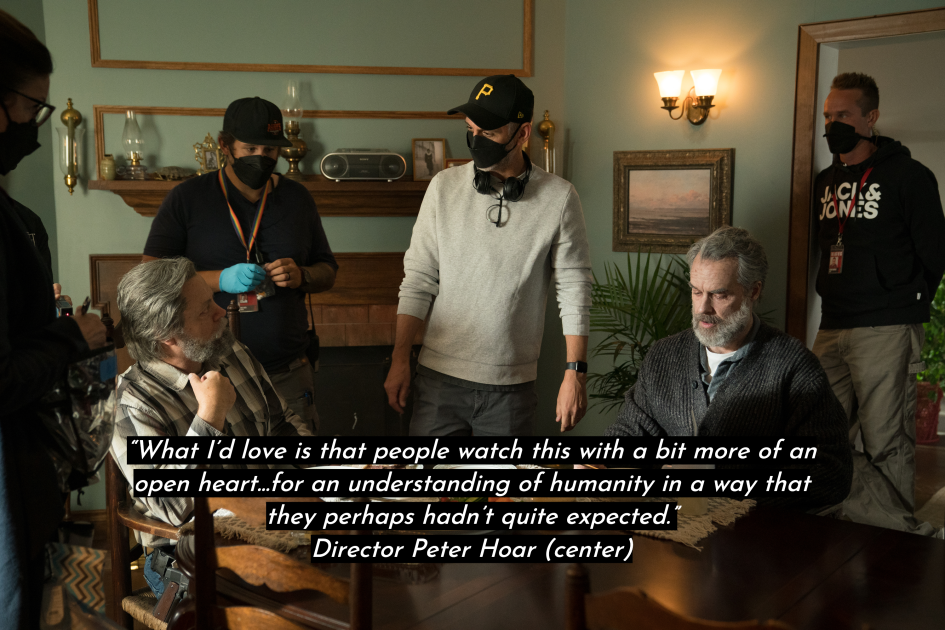

Fans of the series so far, along with fans of the original game, probably understand by now that The Last of Us is not only about the moral choices one man faces during a journey with a girl he barely knows, but about the complexity of humanity during these abnormal times. What makes the series so interesting is its intimate feel, the voyeurism of watching these lives unravel and the expansion of story that allows more examination of different battles being fought before and after the Infection began. The third episode of the series proves that co-creators Neil Druckmann and Craig Mazin are not only interested in providing new audiences with the story of Joel and Ellie, but giving those viewers – along with faithful fans of the game – new stories within the world of The Last of Us. According to director Peter Hoar, early conversations with Druckmann and Mazin centered around this topic, saying “they just dug in, really, and told me what the journey was and why they hoped that the TV show would work alongside the game and what they were doing differently.” The director of photography of “Long Long Time,” Eben Bolter (who also worked as DP on the upcoming fourth and fifth episodes and provided additional photography and second unit shooting on the series for other episodes), shared a similar sentiment regarding the expansion of the characters, stating that he “couldn’t believe how beautiful a story [Druckmann and Mazin had] made, taking the world of The Last of Us and expanding on so many of its themes and characters.” “Long Long Time,” specifically, might start by following Joel and Ellie as they continue their journey, but it doesn’t take long for the episode to shift to 2003, beginning the story of Bill and Frank.

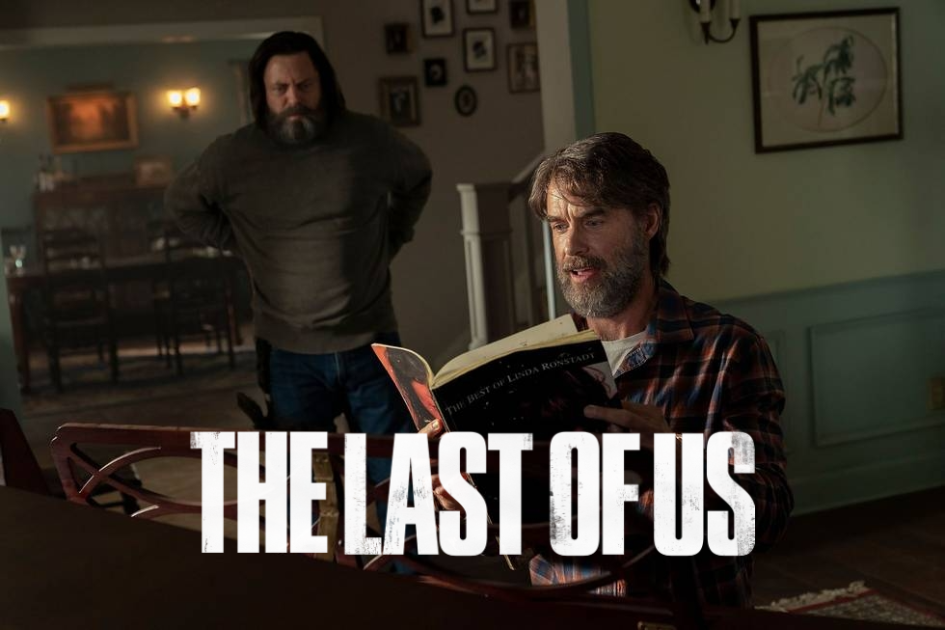

The introduction to Bill is interesting because it gives audiences an immediate sense of who this man is, a man that has waited his entire life for the world to end. Perhaps this sounds hyperbolic, but for a self-proclaimed “survivalist” like Bill, it fits. When the episode shifts back to 2003, at the beginning of the Infection, it shows a neighborhood being rounded up and pushed into trucks. The people of the neighborhood are taken from their homes – well, except one. Bill (Nick Offerman, Parks and Recreation) sits in his secret basement watching live surveillance footage around his house, seeing everyone that lives around him being taken from their homes. There’s an immediate sense of distrust towards the world that’s palpable just by seeing Bill’s mannerisms, his dialogue to himself as the soldiers take his neighbors away. After the soldiers have rounded up everyone and leave, Bill comes out of his bunker and walks onto the street with an exclamation of pure joy. He’s free. He’s waited his entire life for this moment, the freedom that seemingly comes with the end of humanity. As far as Bill is concerned, nothing could be better. He settles into his new life. It provides great amusement to hear Bill’s giggle while watching Infected blow up because of the tripwires he has set. He’s forged his neighborhood into a fortress to keep everyone out, to protect himself, much like he’s probably done in his personal life before the Infection began. Four years pass by and he’s content with his solitude, while the rest of the world is in shambles, until he finds a man in one of his traps outside. He’s fallen into a hole outside of Bill’s fences. After questioning the man and finding out he isn’t Infected nor armed, Bill finds out that his name is Frank. Frank (played here by Emmy winner Murray Bartlett, The White Lotus) is only mentioned in the game, never seen, so this is new territory for everyone watching. Though the episode might seem like a deviation from the game’s story, [director] Peter Hoar doesn’t believe so, saying, “ultimately all we’ve done is just dig a bit deeper; that’s what any adaptation will do.”

Frank convinces Bill to allow him to shower and be fed before moving on to his destination, Bill preparing a beautiful meal for Frank, who makes an offhand comment about “a man who knows to pair rabbit with Beaujolais.” It’s in this interaction that a fire begins to ignite between the two men, Frank beginning to see the real Bill. In the lives of queer people, subtle interactions like this one can mean that one is being seen by another: when Bill responds by saying, “I know I don’t seem like the type,” Frank tells him that he actually does. Even with a short introduction, Bill is clearly a man that is not used to being understood by others. They move into a different room where a piano sits; Frank begins to play and sing “Long Long Time” by Linda Ronstadt, the raw lyrics of which set the tone (and provide the title) of the episode. Bill steps in and begins the lyrics and piano himself, indirectly singing to Frank, “cause I’ve done everything I know to try and make you mine / and I think I’m gonna love you for a long, long time.” This is Bill’s way of allowing Frank to see him, a feat he probably never thought possible. It’s his way of coming out to Frank. It’s his way of allowing himself to stop keeping people out and perhaps giving this one man a chance. The two men embrace, a passionate kiss that leaves Bill almost breathless. Once they’ve moved to the bed, Bill reveals to Frank that he’s only ever been touched by one person, a woman, long ago. While his exact sexual orientation doesn’t matter, what’s significant is that this is probably Bill’s first time expressing an interest towards men to anyone. Even in the apocalypse, being true to oneself can seem a daunting task: Bill shows his courage by allowing himself this moment with Frank. This moment, this day, turns into years as, before they have sex for the first time, Frank tells Bill he’ll be staying for a few more days. The next scene begins with a chyron: “three years later.”

The scene begins with Frank erupting out of the couple’s front door, exclaiming, “Oh, fuck you!” to Bill. The honeymoon phase is over and complications in their relationship have clearly risen to a head. It isn’t that the two are unhappy together, it’s just the nature of relationships being pushed to an extreme by a couple literally only seeing one another. During COVID-19’s early months in 2020, many couples were subjected to a similar situation that kept them secluded from others. Frank is trying to convince Bill to just allow him to tend to the things he finds important in their surrounding area such as gardens and keeping up with certain shops nearby. Frank tells Bill, “paying attention to things: it’s how we show love!” It’s a line of dialogue that says everything about Frank and who he is: how his love is presented, how he expresses his feelings, how he cares for things and people. It’s a difficult scene to see played out, as the reality sets in that even love comes with complications. Bill, even years down the road, is still settling into a life where he involves another person in his decision-making. It’s obvious he isn’t used to this yet, perhaps because he thought this would never be his life. It’s possible that a man like Bill might not have ever envisioned himself being happy with another man, or anyone, due to his self-sufficient nature and obvious introversion. However, there is an obvious change in Bill’s character. He’s protective when it comes to Frank. He gives in to Frank’s wishes because he wants to see his partner happy. He’s been transformed in a way that only love can change someone, the way it sets into someone’s life and makes them feel seen and understood, happy and complete, protective, and protected. The importance of seeing queer love in an episode of a major video game adaptation like The Last of Us on a premium cable channel such as HBO cannot be overstated.

Three more years pass by, bringing the couple (and audience) into 2013. The couple is on a run when Frank tells Bill he has something he wants to show him. Frank surprises Bill with a patch of fresh strawberries. Bill erupts into giggles after taking a bite of the fresh fruit, Frank seemingly thrilled because he knew how happy this would make Bill. Frank is loving Bill the way Bill wants to be loved, the way he needs to be loved. Though they have been together for six years, Frank is still able to show Bill the delights of their chaos-filled world. The two have a bond that has created an entire world between them, a universe where only they exist, a place where they both feel seen by the other. This neighborhood has become the epicenter of their lives together, the place Bill fortified, and Frank stumbled upon. Bill is a hardened man who, seemingly, never expected a life like this, a man like this, a love like this. Would he have found this without the end of the world? Would Bill, a doomsday prepper (or “survivalist” as he tells Joel), have ever let his guard down in the real world with a person of the same sex? It’s in this new world that Bill has found himself able to drop his guard and relent, allowing Frank’s charismatic and charming nature to break through his barriers. He tells Frank, “I was never afraid before you showed up.” This man never thought this was going to happen to him. The Bill that is first on-screen in 2003 is a different man than who is seen a decade later, giggling while eating a fresh strawberry; is this how love changes us?

The last time-jump of the episode thrusts the two men ten years forward into 2023. The scene opens with Frank on their front porch, wheelchair-bound. They’ve known each other for 16 years and now move as one, anticipating the needs of one another. When it comes to the progression of time, cinematographer Eben Bolter said that when it came to the years passing, “we didn’t want to get in the way, we didn’t want to change the aspect ratio or change the lenses or do anything too extreme with the color.” They eat a meal together, Bill making sure Frank takes the medicine to hopefully slow down the progression of the illness that is killing him. Afterwards, they lie down to sleep, but Frank lies awake, thinking. The next day, Frank reveals to Bill what his plan is: death. After moving downstairs, Frank outlines what he wants his final day to look like: he’d like to get dressed up together, get married, and have a beautiful final dinner with a glass of pill-spiked wine that will allow him to drift off peacefully. Bill is clearly heartbroken at the news, Nick Offerman giving the performance of his career in these moments. Peter Hoar commented, “[Nick] pushed himself to places I don’t think he’s ever been.” There is a moment where he looks so overcome with pain that it seems he might not make it another minute, but he pushes forward for his partner. His face contorts with anguish at the thought of such a loss, only agreeing to do as he’s asked after Frank says, “love me the way I want you to.” This is what Frank has been trying to get Bill to understand their entire relationship, what he’s made a point of bringing up over the years in different ways. He’s shown willingness to love Bill the way he needs it, as proven by the thoughtfulness that came with providing him fresh strawberries. Bill would, at one point, have given anything to never see another person again. He was content when his entire neighborhood was taken away in trucks, but the thought of losing this one person, his one person, breaks him. He sees through his own pain and taps into the deep well of love he has for Frank and provides him with one last day. Frank has changed him. Eben Bolter saw Bill’s change in front of his eyes (and lens), commenting that “in the story, this ray of light enters his world. He opens up. He’s vulnerable. He feels things and experiences things that he’s never experienced before.”

In one of the most beautiful montages in recent memory on the small screen, Frank and Bill spend Frank’s final day together around their neighborhood. Max Richter’s beautiful composition “On the Nature of Daylight” plays as the men move around town, get married, and finally sit down to have their last meal together (Bolter said he thought it “would just be a temp score,” noting that he “assumed it would be replaced later in the process and was so moved and delighted that it stuck.”) This scene and this montage (and the entire episode) are edited so beautifully, the scenes cutting at perfect moments that allow an unforced intimacy with the audience. When it comes to the glow of the marriage scene within the montage, Bolter said, “I just saw the opportunity to go really warm and really romantic, to be honest. It just felt right.”

The music only enhances the beauty and devastation of seeing the lovers spend their last day together, only ending when Bill pours Frank his glass of wine and fills it with crushed pills. They both drink a glass before Frank realizes that the entire bottle has been filled with crushed pills, Bill effectively ending both their lives. Frank is initially angry with Bill for this before noting that “from an objective point of view, it’s incredibly romantic.” Bill has decided that he has been satisfied by life, given all he could have ever imagined by meeting Frank that day. It seems that he refuses to live without Frank around every day, refuses to live in a world that involves fear if Frank isn’t going to be there, refuses to live without waking up to the man of his dreams. Bill has been introduced to the possibilities of life through love and won’t face a single day without it. The two men go to their bedroom and close the door behind them, the last time they’re seen on-screen. The audience is granted the ability to watch two queer men decide their own fates in a world that has often tried to kill them.

In the world of cinema, queer characters often die with no warning or clear reason other than shock value or to further the plot through the mental distress of another LGBTQ+ character that has lost their loved one. Many series have come under fire over the years for their queer characters dying (CW’s The 100 comes to mind), LGBTQ+ audiences feeling betrayed after losing their only representation in these types of shows. Peter Hoar hopes this queer-centric episode about love is viewed differently, stating that “what I’d love is that people watch this with a bit more of an open heart because the first two episodes have already set the tone so well for an understanding of humanity in a way that they perhaps hadn’t quite expected.” The Last of Us takes that trope (most commonly known as “bury your gays”) and turns it upside down. Not only does this bottle episode switch gears to pay attention to a character less seen and understood in the game but puts his queerness front and center. The 75-minute episode tells an entire story full of complexity, giving these characters fullness and portraying their struggles, granting understanding with the audience that relationships don’t require perfection to be successful. The most intimate relationships in one’s life can be made easiest by being attentive to the other person’s needs, mostly placing importance in making sure they feel like they are being loved the way they want. It’s in human nature to do things selfishly, but love must not be so. Love is not just for the person who gives it, but also for the person receiving. That person must feel as though they are a priority, that the love they are being given is specifically for them. Frank makes Bill understand this over the years during their relationship, the final punctuation mark in the story of their relationship being Frank asking Bill for the completion of one last favor. Bill’s acceptance and willingness to do this proves the change he’s gone through as a person and lover. He used to live for himself, now he lives (and dies) for Frank.

It’s interesting to think of Bill as someone who might never have found himself without the world essentially ending. He’s a man who spent his entire life getting ready for a disaster that others surely did not believe was coming, who presumably pointed fingers and laughed at people like Bill. A man so isolated that his neighborhood being driven away did nothing but make him smile, Bill was never looking for something like love or someone like Frank. After the Infection began, he was probably content to live the rest of his life in his preserved neighborhood without anyone around. Frank’s appearance outside of his walls is a signal to the audience that he’s opening his doors to someone and inviting them in, against better judgment. He allows Frank entrance, brings him into his home and feeds him. Frank’s permanence in his neighborhood and life isn’t something Bill was ready for, despite his preparation for the hardest days that the planet might face. One can prepare for war against everyone else, can even prepare for isolation for years when prepared for it, but it is seemingly impossible to prepare for the effects love can have on one’s life. It changes everything, alters brain chemistry, infects the host with fear at the thought of losing it. Bill is someone that was prepared for anything he thought life could throw at him, including the world ending and humanity destroying itself, but didn’t realize the emotional toll that comes with loving another. In a letter that Ellie reads aloud to Joel, Bill writes, “I used to hate the world and I was happy when everyone died, but I was wrong because there was one person worth saving.” He wasn’t ready to love, then wasn’t ready to lose.

Self-acceptance is radical, especially in a world that has all but stopped. The courage it takes one to be who they are cannot go unnoticed, and what happens when Bill meets Frank is disarming and unnatural to him. The ability to be oneself when everything else has fallen is almost miraculous, something that Frank teaches Bill. He teaches him that paying attention to things, closely and precisely, introduces one to a way of loving that feels infinite. To feel seen and understood, to be someone’s world, is a feeling that could not be taken away even by a deadly fungus infection. For queer audiences of all ages, “Long Long Time” will serve as a beacon of resilience in the face of danger, a sign of strength in the love that exists between queer men, and the light that can exist in the dimmest situations. The episode joins the pantheon of classic queer storytelling in television, from the entirety of Pose to Black Mirror’s critically acclaimed episode “San Junipero.” While The Last of Us is a series about the moral choices humanity faces and the consequences of the new world, the third episode takes a special interest in telling the specific story of love in a faded world. These men are never treated as expendable, their story – their love – mattering because not only do queer people and their stories matter, but the ability to exist and love freely does as well.

The Last of Us produces 75 minutes of the best television that will be seen all year with its third episode, upending expectations about how the series will faithfully adapt its source material while expanding to create a fresh perspective. The episode will produce tears, create discussions around the attentiveness to love, and will certainly go down as one of the most heartbreaking episodes of television this decade (or any). It’s okay to scream or cry or even be angry because of the episode, but… from an objective point of view? It’s incredibly romantic.

Episode three of The Last of Us, “Long Long Time,” is currently available to stream on HBO Max.

Photos by Liane Hentscher/HBO

14th Guild of Music Supervisors (GMS) Awards: ‘Barbie,’ ‘Daisy Jones and the Six’ Lead Wins

14th Guild of Music Supervisors (GMS) Awards: ‘Barbie,’ ‘Daisy Jones and the Six’ Lead Wins  38th American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) Awards: ‘Oppenheimer’ Wins Feature Film Prize

38th American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) Awards: ‘Oppenheimer’ Wins Feature Film Prize  71st Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) Golden Reel Awards: ‘Oppenheimer,’ ‘Maestro,’ ‘Society of the Snow’ Top Film Wins

71st Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) Golden Reel Awards: ‘Oppenheimer,’ ‘Maestro,’ ‘Society of the Snow’ Top Film Wins  74th American Cinema Editors (ACE) Eddie Awards: ‘Oppenheimer,’ ‘The Holdovers’ Take Top Film Honors

74th American Cinema Editors (ACE) Eddie Awards: ‘Oppenheimer,’ ‘The Holdovers’ Take Top Film Honors